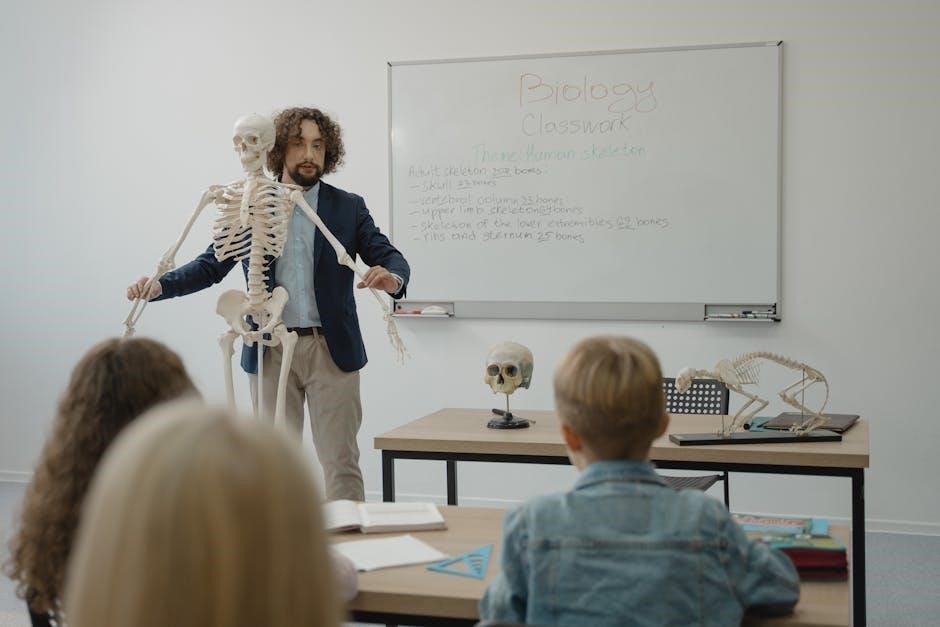

The skull, a complex skeletal framework, provides crucial head and face structure. Composed of cranial and facial bones, it protects the brain and supports sensory organs.

Understanding skull anatomy is vital for medical professionals, anthropologists, and students alike, offering insights into human evolution and individual identification.

Overview of the Skull

The skull represents a remarkable biological structure, serving as the foundational support for the head. It’s not a single bone, but a complex assembly of 22 distinct bones – eight cranial and fourteen facial – intricately joined by immovable joints called sutures. These sutures, like the coronal, sagittal, and lambdoid, are crucial for accommodating brain growth during infancy and childhood;

The skull is broadly divided into two main sections: the neurocranium and the viscerocranium. The neurocranium, or braincase, encases and protects the delicate brain, while the viscerocranium, or facial skeleton, forms the framework of the face, providing attachment points for muscles involved in facial expression and mastication (chewing).

Its overall shape varies between individuals, influenced by factors like age, sex, and ancestry. Studying the skull’s morphology provides valuable information in fields like forensic anthropology, aiding in the identification of individuals from skeletal remains. Furthermore, numerous foramina (holes) and fissures (clefts) punctuate the skull, allowing passage for nerves and blood vessels essential for head and brain function.

Functions of the Skull

The skull performs a multitude of critical functions extending far beyond simple structural support. Primarily, it provides robust protection for the brain, safeguarding this vital organ from mechanical injury. This protective role is enhanced by the skull’s rigid structure and the cushioning effect of the meninges and cerebrospinal fluid.

Beyond brain protection, the skull supports the delicate sensory organs – eyes, ears, nose, and tongue – housing them within bony cavities. It also serves as the attachment point for numerous muscles of the head and neck, enabling facial expressions, head movements, and mastication.

The skull’s foramina and fissures facilitate the passage of cranial nerves and blood vessels, ensuring proper neurological function and cerebral perfusion. Furthermore, the nasal cavity within the skull warms, filters, and humidifies inhaled air. Finally, the skull contributes to vocal resonance, impacting speech production. Its complex design reflects a remarkable interplay between protection, sensory support, and functional capabilities.

Cranial Bones: Neurocranium

The neurocranium, or cranial vault, encases the brain. It’s formed by eight bones: frontal, parietal (two), temporal (two), occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid.

Frontal Bone

The frontal bone forms the anterior portion of the cranium, contributing to the forehead and the upper parts of the orbits – the bony sockets that house the eyes. This single bone is characterized by its roughly rectangular shape, though variations exist between individuals.

Key features include the glabella, the smooth area between the eyebrows, and the frontal sinuses, air-filled spaces within the bone that contribute to voice resonance and reduce skull weight. Superiorly, the frontal bone features the superciliary arches, bony ridges above the eyes, and the frontal eminences, slight bulges.

Articulations are crucial; the frontal bone connects with the parietal bones via the coronal suture. It also articulates with the sphenoid, ethmoid, and nasal bones. The supraorbital foramen and notch allow passage for nerves and vessels supplying the forehead and upper eyelids. Understanding the frontal bone’s anatomy is essential for interpreting facial expressions and recognizing potential fracture sites.

Parietal Bones

The parietal bones, typically paired, form the majority of the sides and roof of the cranium. These large, flat bones contribute significantly to the braincase, providing protection for the cerebral cortex. Their shape is roughly quadrilateral, curving gently to conform to the cranial vault.

Each parietal bone features several important markings. The superior temporal line and inferior temporal line serve as attachment points for muscles involved in chewing. The parietal foramen allows passage for emissary veins, connecting the scalp with the dural venous sinuses inside the skull.

Parietal bones articulate with multiple other cranial bones: the frontal bone anteriorly via the coronal suture, the occipital bone posteriorly via the lambdoid suture, and the temporal bones laterally. These sutures are fibrous joints that allow for slight movement during birth and growth. Variations in parietal bone size and shape are common, contributing to individual skull morphology.

Temporal Bones

Temporal bones are paired bones located on the sides and base of the skull. They are complex in structure, contributing to the cranial floor, lateral skull walls, and housing structures of the inner ear. Each temporal bone consists of several parts: squamous, petrous, mastoid, and tympanic.

The squamous part forms the lateral skull wall, while the petrous part houses the middle and inner ear structures, including the cochlea and semicircular canals. The mastoid process, a prominent projection, serves as an attachment point for neck muscles. The tympanic part surrounds the external acoustic meatus (ear canal).

Key features include the mandibular fossa, which articulates with the mandible (jawbone), and various foramina for cranial nerves. The temporal bones articulate with the parietal, occipital, and sphenoid bones. Their intricate structure is crucial for hearing, balance, and facial nerve function. Variations in temporal bone morphology can impact these vital sensory systems.

Occipital Bone

The occipital bone forms the posterior part and base of the skull. It’s a single bone, unlike many others which are paired, and plays a critical role in protecting the foramen magnum – the large opening through which the spinal cord connects to the brain. This bone articulates with the parietal bones via the lambdoid suture.

Key features include the external occipital protuberance, a prominent bump on the posterior surface serving as muscle attachment, and the superior nuchal lines extending laterally from it. Inferior nuchal lines are also present, providing further attachment points for neck muscles.

Internally, the occipital bone contributes to the cranial fossa, housing parts of the cerebellum and brainstem. Several foramina, like the hypoglossal canal (for the hypoglossal nerve), are present. The occipital condyles articulate with the first vertebra (atlas), enabling head nodding movements. Variations in occipital bone shape can influence spinal cord compression risks.

Sphenoid Bone

The sphenoid bone is a complex, bat-shaped bone situated at the skull’s base, articulating with all other cranial bones. Often described as the “keystone” of the cranium, it contributes to the cranial floor, lateral skull walls, and orbits. Its intricate structure houses numerous foramina, serving as passageways for nerves and blood vessels.

Key features include the sella turcica, a saddle-shaped depression housing the pituitary gland, and the greater and lesser wings extending laterally. The pterygoid processes project inferiorly, providing attachment points for jaw muscles. Several foramina, such as the foramen ovale and foramen rotundum, transmit cranial nerves.

The sphenoid bone’s internal structure features air cells (sphenoidal sinuses) reducing skull weight. It forms parts of the optic canals, allowing passage of the optic nerves. Fractures to the sphenoid bone can have severe neurological consequences due to its central location and proximity to vital structures.

Ethmoid Bone

The ethmoid bone is a lightweight, irregularly shaped bone located between the orbits, contributing to the nasal cavity, orbits, and cranial floor. It’s a crucial component of the nasal septum and lateral nasal walls, playing a vital role in airflow direction and humidification.

Distinctive features include the cribriform plate, perforated with olfactory foramina allowing passage of olfactory nerves, and the perpendicular plate forming the superior nasal septum. The superior and middle nasal conchae (turbinates) project into the nasal cavity, increasing surface area for warming and moistening inhaled air.

The ethmoid bone contains ethmoidal air cells (sinuses) reducing skull weight and contributing to voice resonance. Its complex structure forms parts of the orbit, housing the lacrimal groove for tear drainage. Fractures can lead to cerebrospinal fluid leaks due to its proximity to the cranial cavity.

Facial Bones: Viscerocranium

Facial bones, forming the viscerocranium, create the face’s framework. These bones support facial features, protect sensory organs, and provide attachment points for muscles of facial expression.

Maxilla

The maxilla, or maxillary bone, forms the upper jaw and a significant portion of the face. Paired bones, they contribute to the hard palate, nasal cavity floor, and orbits (eye sockets). Each maxilla articulates with numerous other cranial and facial bones, including the frontal, nasal, zygomatic, palatine, inferior nasal conchae, and vomer.

Key features of the maxilla include the alveolar process, which houses the upper teeth; the infraorbital foramen, transmitting the infraorbital nerve and vessels; and the maxillary sinus, a large air-filled space that lightens the skull and contributes to voice resonance. The maxilla’s complex structure is crucial for mastication (chewing), speech, and facial expression.

Clinically, the maxilla is relevant in dental procedures, facial trauma, and sinus infections. Fractures of the maxilla can occur due to significant force, and the maxillary sinus is prone to inflammation and infection. Understanding the maxilla’s anatomy is essential for diagnosing and treating various conditions affecting the face and oral cavity.

Mandible

The mandible, commonly known as the jawbone, is the largest and strongest bone of the face. Unlike most skull bones, it’s a single bone, not paired. It articulates with the temporal bones at the temporomandibular joints (TMJs), enabling jaw movement for chewing, speaking, and facial expressions.

The mandible consists of a body, a ramus, and a chin (mental protuberance). The body forms the horizontal portion, housing the lower teeth in the alveolar process. The ramus ascends vertically, connecting to the body and forming the TMJ. Important features include the mental foramen, transmitting the mental nerve and vessels, and the mandibular canal, housing the inferior alveolar nerve and vessels.

The mandible plays a vital role in mastication, speech, and maintaining facial form. Fractures of the mandible are common due to its exposed position, and TMJ disorders can cause significant pain and dysfunction. A thorough understanding of the mandible’s anatomy is crucial for dental, surgical, and orthodontic interventions.

Zygomatic Bones

The zygomatic bones, often called the cheekbones, are paired facial bones forming the prominences of the cheeks. They contribute to the lateral walls of the orbits (eye sockets) and play a crucial role in facial aesthetics and structural support. These bones articulate with the frontal, temporal, maxilla, and sphenoid bones, forming key facial features.

Each zygomatic bone comprises several important features, including the temporal process, which articulates with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone to form the zygomatic arch. The zygomatic arch provides attachment points for facial muscles involved in chewing. The zygomaticofacial foramen, located on the lateral surface, transmits branches of the zygomatic nerve.

Zygomatic fractures are relatively common, often resulting from facial trauma. Understanding the intricate anatomy of these bones is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of facial injuries, as well as for reconstructive surgical procedures. They contribute significantly to facial expression and overall skull morphology.

Nasal Bones

The nasal bones are two small, rectangular bones forming the bridge of the nose. They are located at the top of the nose, articulating superiorly with the frontal bone and laterally with the maxillae. These paired bones provide initial support for the nasal cartilage, shaping the external appearance of the nose.

Each nasal bone features two surfaces and four borders. The external surface is smooth and convex, contributing to the contour of the nose, while the internal surface is concave, forming part of the nasal cavity. The superior border articulates with the frontal bone, and the lateral borders connect with the maxillae. The inferior border forms the apex of the nose.

Nasal fractures are among the most common facial fractures, often occurring due to trauma. Due to their superficial location, the nasal bones are particularly vulnerable to injury. Understanding their anatomy is crucial for proper diagnosis, reduction, and management of nasal fractures, ensuring both functional and aesthetic restoration.

Skull Features & Markings

The skull exhibits numerous foramina and fissures, serving as pathways for nerves and blood vessels. Sutures, fibrous joints, connect cranial bones, allowing for brain growth.

Foramina and Fissures

Foramina and fissures are crucial openings within the skull, serving as vital passageways for nerves, blood vessels, and ligaments. These openings punctuate the bony structure, facilitating communication between the cranial cavity and the external environment.

The foramen magnum, a large opening in the occipital bone, allows the spinal cord to connect to the brain. Several smaller foramina, like the optic canal and superior orbital fissure, transmit cranial nerves responsible for vision and eye movement.

Fissures, generally larger and irregular openings, such as the pterygopalatine fossa, accommodate multiple structures. The jugular foramen allows passage of the internal jugular vein and several cranial nerves. Understanding the precise location and contents of each foramen and fissure is essential for neurological diagnosis and surgical planning.

These markings aren’t merely holes; they represent critical anatomical landmarks, influencing neurological function and providing pathways for essential physiological processes. Their study is paramount in comprehending the skull’s complex architecture.

Sutures of the Skull

Sutures are fibrous joints uniquely connecting the bones of the skull. Unlike movable joints, sutures are largely immobile, providing crucial protection for the delicate brain. These interlocking, irregular edges gradually fuse throughout life, enhancing cranial stability.

Key sutures include the coronal suture, separating the frontal bone from the parietal bones; the sagittal suture, uniting the two parietal bones; and the lambdoid suture, connecting the parietal and occipital bones. The squamous suture joins the temporal and parietal bones.

In infants, sutures remain flexible, allowing for brain growth and facilitating childbirth. These unfused areas, known as fontanelles, eventually ossify. Sutures also accommodate slight cranial deformation during delivery.

The pattern and degree of suture closure can provide valuable information regarding age and potential developmental abnormalities. Studying sutures is vital for forensic anthropology and understanding cranial development throughout the lifespan, offering insights into individual history.